It should not come as a surprise that Elias Canetti, in his monumental Crowds and Power (1960), has something to say on parliamentary democracy. After all, democracy is a mass phenomenon and a way to control access to power. His remarks concentrate on the two-party system. This system uses, Canetti explains, “the psychological structure of opposing armies”. Each political party is aiming at victory, deploying an offensive strategy, while at the same time trying to avoid defeat and minimize losses. “It is will against will as in war.”

However, the parliamentary arena is not a real battlefield, Canetti concedes, thanks to the fundamental principle of immunity. The members of the outvoted party can readily admit defeat and accept the majority decision because, as long as the parliamentary system is working properly, they may be sure not to be punished or killed by their victorious opponents. Their immunity from physical violence – and more particularly from revengeful death – allows them to be politicians, acting as fearless gladiators of argumentation. Immunity, of course, extends to both sides, protecting the winners as well as the defeated party. All members of a parliament, being equals, “share in a like immunity”, Canetti explains. This also assures that opposition never leads to punishment. Being able to vote freely, according to ones principles and specific convictions, without any fear of lethal consequences, is essential; the parliamentary system will ‘crumble’, Canetti states, as soon as but one member brakes the rule of immunity. Decision-making by way of free voting implies that democracy as a system depends on “the renunciation of death as an instrument of decision”.

It is not farfetched to conclude on the basis of Canetti’s views that, if some individual or group in a parliament ‘merely’ threatens to seriously harm his equals (or advocates the violent storming of the parliament), the fundamental principle of immunity is broken just as well. The logic of voting is then discarded for the logic of warfare: forcing a decision through killing (or the equivalent there-off). It all comes down, Canetti concludes, to accepting the two figures representing the result of a vote: “anyone who tampers with these figures, who destroys or falsifies them, lets death in again without knowing it. Militarists who mock the ballot only betray their own bloodthirsty proclivities.”

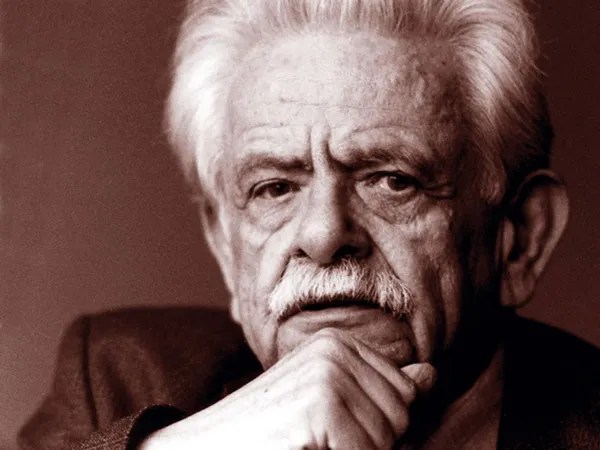

Elias Canetti spent many of his best working years to write Crowds and Power. Although this is a post-war book, looking back in bewilderment on the massive support for the nazi campaigns (in propaganda, in warfare, in racial purging and extinction) the number of pages actually dealing with the nazi-period is limited. That may surprise us, but only for a while. Canetti’s goal is not to chart the workings of the SS Hauptmann’s pathetic psyche, nor to explain the strategic secrets of Hitler’s rise to power. Crowds and Power is all about demonstrating why and when our most basic and most primitive instincts take back control on how we act and who we are. Look, Canetti seems to be saying on almost every page, just look how primitive we humans really are, look how strongly inclined we still are to solving disputes through violence. The political principle of democratic immunity is an ample demonstration of the frailty of our civilization. It also demonstrates that the frail is the essential.